|

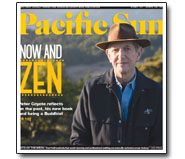

PACIFIC SUN - April 23, 2015

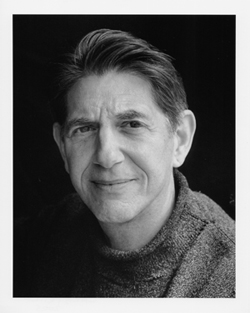

Peter Coyote reckons with his

life as actor, author, activist, priest, and

soon-to-be Marin expatriate

So, why another book from you? You covered a lot

of ground in your previous one …

Yeah, and especially why another memoir in

particular, right? Well, when I looked back at my

early life more recently, I realized I had been

operating under a world view that was not exactly

accurate—I thought there were just two options—a

world of love or a world of power—and the trick was

to somehow get the mix right. Love without power is

flaccid; power without love is brutal. I had all

these mentors who have taught me about the world,

taught me about navigating the realms of love and

power, and from a conventional point of view I’d say

I did alright—it’s not an exaggeration to say that

for a time I was an international movie star, maybe

not of the first magnitude, but my film

"A Man in Love"

did open the 40th anniversary of the Cannes Film

Festival. But it was wanting.

Luckily, I had grown up in the household of a very

rich man, in which I don’t remember anybody being

happy. So that liberated me from being attached to

the idea that true wealth was going to be material

in nature. At about age 29, I met Gary Snyder, and

he was such an exemplar of an integrated life that I

was floored. I couldn’t figure out at first what the

trick was, how he linked his family life, his

political life, his artistic life, his fame, his

family life—all of it, until I realized that

Buddhism and Buddhist practice was at the core.

Did you start involvement with Buddhism soon

after meeting Snyder?

Not immediately, but maybe five years after I met

Gary I began courting a woman who was living at Zen

Center, whom I subsequently married, and I began

formal Buddhist practice. And I didn’t really stick

to it diligently for a long time, you know. I was

building a career—I didn’t get my Screen Actors

Guild union card until I was 39—and I had a daughter

to get through school, and we had to save for

college, then we had a son. Also, I had chosen a

wife who did not want to live in the back of a

truck, so I put a lot of energy into earning a

living even though it didn’t engage me all that

much.

Do you mean that you really weren’t that into

acting?

It was never my greatest gift. I’m a much better

writer than I am an actor. I might have been a

better actor had I had time to really study, but I

started late and couldn’t take a year off to go to

England, which I would have liked to do. So in some

ways, when I was performing, I always felt a little

naked and exposed. I came to understand that because

of my childhood I had been really traumatized when I

was little and that the way I learned to survive was

by cutting off my feelings, and learning to see

things in a clear observational, unemotional way. It

helped me then, but it’s an impediment to being an

actor because it often took me a long time to figure

out exactly what I was feeling—and knowing what you

are feeling is a prerequisite for a great actor. You

don’t actually have to be smart, but you can’t act

unless you have ready access to your feelings. And I

don’t. It’s not easy for me. Even today when I see a

script where somebody breaks down in tears, more

than half the time I’ll just turn it down. It’s too

much work.

But you must have enjoyed some of it, even though

you stayed in Marin instead of moving south.

I love the camaraderie of acting, the rehearsing,

the problem-solving, but the business of making

films is so noxious and fraught with horseshit and

ignorance. In fairness, either through lack of

talent or age, I could never get to the level I

wanted to get—I was 40 when I began, and it’s a

kid’s game. I could never quite get access to the

great scripts and roles, so by the time I was about

50 my opportunity to be a star with access to them

had run out. I was getting the leavings, and I think

because I wouldn’t live in Hollywood and didn’t have

a publicist and didn’t go to film openings and all

that, I was just not in the central corridor of the

industry. It did bother me sometimes, as I couldn’t

get access to the best stuff, but it didn’t bother

me enough to move to Los Angeles, and live a ‘film’

life. I figured that I really lived much more time

offstage than on and that that was the life I ought

to take the best care of.

Your new book is very much a frank reckoning with

your difficult childhood and youth. Not to be too

therapist-like here, but do you think you were

afraid of really accessing and showing your feelings

in acting because that was just too frightening for

you?

I don’t know if it was threatening, but I didn’t

have any technique to do it. If I couldn’t

intuitively grasp what was being asked of me in a

role, I was in trouble. So I didn’t seek the

challenges as an actor, and every role made me feel

as if I’d just gotten away with it. I was very lucky

they came to me a lot. I’ve done over 140 films for

the screen and TV, but I just never felt fully

engaged as an actor.

But you did achieve fame. What was that like for

you?

You know, I’m vain enough to want to be famous for

something. I wouldn’t mind being famous for being a

good writer. When I won a Pushcart Prize, for

Carla’s Story, I thought, ‘Holy shit, Raymond

Carver, John Updike and Saul Bellow won Pushcarts!

Wow!’ That’s good company, so yes I’m proud of that.

But just because somebody’s seen you on television,

and they elevate you to the pantheon of the

cheeseball celebrities on the cover of tabloids in

the supermarkets? Gag me. Once I was in Spago with

my first wife and we were having a really tough time

and she was openly weeping, and here comes a woman

with a pad and pencil and a big grin, hanging

expectantly over my shoulder indicating she wants an

autograph, and I said to her, ‘Are you f—g crazy?

Can’t you see my wife is in tears? That this is not

a good time?’ Well, that’s no recipe for good

manners or stardom, but people will approach you at

any time and you’re expected to be charming. I had

kids at home and some guy published my home address

in a fan magazine without a thought about the risk

it might cause. So I don’t care about the fame other

than being able to meet who I want to and getting

into a restaurant I want to try, and occasionally

shining a light on an important issue. Other than

that, you can have it.

I recall when you and I were having lunch in

Tiburon years ago, a kid followed us out to our

cars, and asked if he could take your photo, and

then asked, “So, who are you again? I know you are

famous but I don’t know just who you are.” It seemed

a perfect illustration of the emptiness of fame.

There you have it!

You have also had a good career using your voice

for many things, too—that seems a great way to not

be visibly recognized.

Yes, that worked for a long time, but Ken Burns

sorta took that anonymity away and now everybody

recognizes my voice—I joke that he killed my career

as a bank robber. But once Christopher Reeves, rest

his soul, asked me, ‘Peter, how do I break into this

voiceover market?’ And I had to say, ‘Well I’ll tell

ya, Chris, as soon as you tell me how to break into

the multi-million dollar salary racket!’ I mean, how

much does anybody need? Why not leave something for

all the guys like me who are not making big money as

an actor and have tuition, mortgages and bills to

pay?

“How much do you need?” seems a crucial question

nowadays.

Indeed. For me, I am actively lowering my lifestyle

right now. I make about 20 percent of what I used to

make. I got rid of my fancy car and drive a Chevy

Volt; I’m buying a house with half the proceeds of

what I sold my Mill Valley house for. The new place

will need some work on it and I will have to work

myself for that, but I don’t mind working for

something specific. I just don’t want to work when I

don’t have to anymore. My kids graduated debt free

and are doing well. I’m 73 years old. It goes by

very fast, let me tell you.

I already agree. Back to your book—your father

was a powerful but distant guy, your mom seems to

have been fragile, and it reads like you were

looking for other parents, other family for a long

time—and that your childhood had a big impact on

your marriages and relationships with women.

When I was a little kid, my mom had a nervous

breakdown and she was a ghost for a couple of years,

and I think it triggered this little ‘make the mommy

feel better’ gland. And it’s so convenient, to

always be helping others. It makes you feel needed,

powerful even, and you don’t have to worry about

your own problems. I’ve given that up. It only took

50 years. There was nothing truly wrong with the

women in my life; it was more my feeling that I was

somehow responsible for their suffering or helping

them.

You also wrote that your need for lots of

solitude also made relationships hard for you.

I think my wives could never really grasp what a

hermetic person I am. When I was working on this

book, one day my wife said, ‘You’re just hiding out

from life.’ True, I’d go to my office all day every

day, and swim around in my thoughts and memories to

write. But getting this book out was like crapping a

porcupine.

You wrote that reading—a solitary pursuit— has

always been crucial to you.

Yes, when I was in 4th grade, I went to a lovely

little school called the Elizabeth Morrow School in

Englewood, New Jersey, and my desk was back in the

far left corner next to a bookshelf of little orange

books that must have run 15 feet—biographies of

famous people mostly—and I resolved to read them

all. Then there was a series called the Landmark

Books, and I read them all. Then the Oz books and I

read all those, too. Then Lad of Sunnybrook Farm,

and the Black Beauty series, and I never stopped. I

think what I found in books was a freedom in my

imagination that I could not find in my physical

life. My parents were hyper-vigilant, always worried

about me. My mom worshiped Sigmund Freud and got

everybody in the family but herself into analysis.

She was always scanning me for potential problems or

telling me what I was really thinking and feeling

and it made me very angry. She sent me to therapy

when I was 11 and one day the therapist asked me,

‘Why are you here?’ and I said, ‘Well, I do this,

and this, and this,’ and ran down a litany of

complaints that my parents complained about. And he

said, ‘Yeah? And who is that a problem for?’ and I

said, ‘Well, it’s a problem for my parents,’ and he

said, ‘OK, you go home and send your parents in to

see me!’

Sometimes it takes many years to get some

perspective on those childhood family influences …

Just last fall, I was visiting a wonderful therapist

I check in with once in awhile just to touch base

and he said to me, ‘You do know your parents were

crazy, don’t you?’ And I said, ‘Oh sure, yeah …’ And

he said, ‘No—your parents were crazy, certifiable.

It was as if God asked himself, ‘How can I give this

boy the toughest adolescence possible?’—because

that’s what you had.’ And I felt this strange sense

of relief, as if my life had been seen.

You really do lay yourself bare in this book.

Why write otherwise? I think that as long as you

don’t take cheap shots, especially against those who

can’t answer back, you should tell the truth. And,

like in acting, if you are really specific and

honest, some elements become universal in a funny

way.

You write movingly of your mother’s death, in a

hospital, and how a nurse offered in a crudely timed

manner to “help” her die sooner. It’s a striking

story, as this issue of “assisted dying” is in the

news right now, with possible legalization in

California coming. Any thoughts on that?

I think you have to begin with the observation that

everything has a ‘shadow’—so while I agree with the

concept, there will be people who may take advantage

of this in certain ways—let’s save the estate by

getting mommy gone a little earlier, and so forth.

But it comes down to the question of whether or not

a person has the right to control their manner and

time of their death. If you ask me as a Buddhist

teacher, I am categorically against suicide. But the

world is not my student and that is just my opinion.

So if somebody is wracked by pain and there is no

way out, they are not going to get better, and they

choose to start over or—as the Dalai Lama once said,

‘Change their clothes,’ I don’t think it’s my

business. It’s like abortion—I don’t have a womb,

and so I stay out of the debate, except to support

the right of women to make their own choices. Some

women would think nothing of sacrificing a son to

the military in a fruitless war, but would never

consider an abortion for any reason. That’s curious

to me. Of course there would need to be safeguards

in place and all that, but nothing will ever be

foolproof and we have to accept the errors along

with the choice. Which is why I’m against the death

penalty.

You were close to Robin Williams. Any thoughts on

his dying?

I wrote a piece online that went viral, about

Robin’s great gift. Likening it to a thoroughbred

horse of near magical ability. The problem was that

it was never adequately trained. Sometimes he would

get on it and it would take him (and us) into

magical dimensions, but at other times it took Robin

where it wanted to go. That was the great tragedy

for me, that his greatest gift actually killed him.

Had he had some sort of spiritual training, he might

have been able to wait out the bad period he was

going through, but he was always in the saddle, and

this trip took him over a wall with nothing on the

other side.

In your first book you wrote at length about your

role in the Diggers, prototypes for the whole

Haight-Ashbury ’60s scene. Are you still in touch

with any of them?

Certainly. In fact, just last year I called all the

surviving Diggers and Free Family folks together—108

of them. I wanted to organize a relief effort to

help some of our members who were old and poor—about

six of them. I tried first on the Digger website,

asking people to why not list their skills—if I need

a lawyer or plumber, why not a Digger lawyer or

plumber? And people got really indignant and angry

with me for dealing with money. Even old and very

dear friends I really respect. I tried to point out

that if we were candid, the Diggers were like an art

project—we were never the model of a viable

alternative economy. We were living off welfare

payments to mothers with children, selling dope,

bartering, doing all sort of things including

thievery.

So I decided that I was not going to fight my oldest

friends, and I apologized, saying that I understood

that this had become sort of a religion and

apologized for being insensitive. I started a new

site called the Free Family Union, and virtually

everyone came over. So one thing I learned is that

everybody has their own reasons for joining a group,

and they may not see it the way you do even if you

started it. Most everyone in this group now lived in

the world, made money, paid taxes, but they had this

idealized memory of the Diggers as a place of

purity. It’s a common delusion that there’s some

other world other than this one with all its warts

and angels where we can live. Well, my Buddhist

practice has informed me that there is no pure place

outside of the world to stand—the world is exactly

what it is, and if you can’t find your happiness and

joy in this world, with ISIS, with Hitler, with

Mother Teresa all mixed up in it, you’ll never find

it. What a shame, to pass up the opportunity for joy

because it feels trivial or inadequate next to the

suffering of others—who are searching for joy, by

the way. So once the new group got rolling, I backed

out a little—and this goes back to another downside

of “fame”—that you become a touchstone for people’s

projections and ideas of you. They still come to me

either overly deferential, or as if they perceive me

thinking that I am a big deal and it is their job to

take me down. It smothers you in thoughts and can

get tiresome. So I find things work really well

without me, and I just participate like anybody else

when I feel like it. And we are supporting six

people, giving them each about $200 a month. It’s a

big bump of grace to people living solely on Social

Security, and I wish we could do more.

On a broader level, how about the whole ’60s

idealism, what it all might have meant in the longer

term? I mean, the “revolution” did not happen, but

some lasting impacts seem to have occurred …

That’s right. In the ’60s, you could say we lost

every political battle. We didn’t end capitalism,

racism, war, violence, we didn’t create a world of

love and peace, and we just have to accept that.

But, it’s also true that we won every cultural

battle. There’s no place in the U.S. today where

there is not a women’s movement, an environmental

movement, civil rights, and so on. Paul Hawken, in

his book Blessed Unrest, pointed out that if you

aggregate all these little or big individual

struggles, it’s the largest mass movement in the

history of the planet. There’s also no place you can

go where there are not alternative spiritual

practices—yoga, Buddhism, organic or slow or local

food are spreading—these things exist in the realm

of culture and that realm is much deeper than

politics. And when people have lives that are

meaningful to them they will hold and defend them.

Back then, the Diggers couldn’t believe people would

throw themselves onto the barricades to become part

of Marx’s lumpen proletariat, but today I’m watching

farmers in Nebraska fighting for their water,

watching people fighting to keep big-box stores out

of their towns, to stop fracking, all over the

country. So we were cultural warriors, and I take a

lot of pride in the changes we started. It’s not the

end of the battle by far—this generation and others

will have their own struggles, but we played for

keeps, gambled everything, and we moved the marker

an appreciable amount.

Perhaps the most visible mark of that is a black

president, something unimaginable not so long ago.

Yes, and yet there is still a huge population who

cannot stand the thought of a ‘N—r in the White

House.’ He gets a huge number of threats every day.

People with guns stalked around his early speeches.

What do you imagine might have happened if the Black

Panthers had shown up armed to a Reagan speech? It

would have been a bloodbath. Anyway, he might not be

the black president I might have wanted, but I

admire him, and I’m not in the hot seat with him and

so I temper my judgments a bit because I remember my

days on the Arts Council and some of the flak you

get for anything you do. That’s not a pass by any

means, but … that’s a whole other subject.

Drugs were a big part of the ’60s, and of your

own life. Any lessons there?

I was addicted to just about everything. We made a

lot of mistakes there. But I can remember

superficially how and why so many of us got into

hard drugs. If you’ve taken on the charge of

imagining a new world and acting it all out, one

thing you have to demand of yourself is, ‘Suppose my

imagination has actually already been tamed,

colonized, and all my grand visions and plans are

simply permitted within the parameter of a bigger

field that just appears to be liberated, but is

still inside the fence of the majority culture’s

values?’ That was a very scary thought. So one of

the ways you could test yourself was to take

substances—speed, heroin, cocaine, acid, DMT and

STP—substances the establishment was terrified of.

And of course when you do that in your 20s you have

no idea of the toll it will take on your body and

health. Acid was different, though. Everybody I knew

who took acid took it as a kind of spiritual

pilgrimage. What we never anticipated was that the

next generation would take it to trip at the mall

and that it would become a spreading, indulgent,

sensual party, stripped of spiritual dimensions.

There has never been a drug law in this country,

since the Civil War morphine laws, that has not been

based on bullshit. Every one of these ‘expert

panels’ convened to study the subject, from

LaGuardia through Nixon and Kennedy have said,

‘Forget the drug war,’ decriminalize it, help people

kick or give them maintenance doses so they can

contribute to society. Even the drug pushers want

the ‘risk premium’ that raises the prices of drugs

due to their illegality.

Music was another huge part of those times, and

you write about being very into playing and

listening from a very early age. Years back I heard

you do a whole set of what you called “country death

rock” at the old Sweetwater. Are you still playing?

Music is a huge part of my life. I’d probably

believe in God if I’d only been given the talent to

be a professional musician. I was playing guitar for

two hours today before I came to meet you! But it’s

not my gift. We had a six-bed bunkhouse in the Olema

commune and musicians would come out and stay, like

Paul Butterfield and Michael Bloomfield, and we’d

stay high and play music for days. And in the book I

recall hearing sax greats Al Cohn and Zoot Sims

playing in my house, and it was the first time I’d

seen grown-up people having so much fun.

Your book starts and ends with you in Zen

sesshins—extended, intense meditation retreats—some

40 years apart, at Green Gulch. In the latter, the

more recent one, you relate a profound experience, a

sort of breakthrough as it seems. But you don’t name

it.

Yeah, the Japanese call it a ‘kensho’ experience,

but right, I didn’t want to name it. When I started

out in Zen, that was the thing to strive for, and if

I could get that, I thought I’d never be

uncomfortable, awkward —I’d be enlightened, the

coolest guy in the room. Somewhere along the line

that notion falls away, and you realize that if you

have an idea of yourself over here and enlightenment

over there and they are separate, they are never

going to come together. The truth according to the

Buddha, is that we are all enlightened, that it is

our basic nature, but we don’t or can’t pay

attention to it, or even believe in it. So the

second thing that happens when you have an

experience like that is that you understand that it

is not so important after all. Nobody really cares

about my personal experience. What they might care

about is how I live my life—am I kind,

compassionate, helpful, vigorous, wise? And if I’m

not, what difference does my personal enlightenment

really make? I wondered if I might get some blowback

or distort the meaning of the experience by

describing it, but I discussed it with my Zen

teacher, and he said, ‘Sure, include it.’ But more

important is what he first said when I reported it

to him, which was, ‘Don’t try to hold onto it!’

What did the actual process of taking vows and

becoming a priest entail for you?

First, I would never put myself forth as a teacher

of any kind, because I could never think of how to

do it without my stepping forward becoming an

expression of ego. One of the reasons I became a Zen

Buddhist was because of the custom of

‘transmission’—that you don’t teach independently

until you are given permission to teach by your

teacher and by the students you have been practicing

with. And that saves you from being one of the guys

who just show up and announce that they are gurus,

set out their shingle. A lot of abuses stem from

that. So at a certain point my teacher told me it

was time to start teaching, and when I demurred that

I was not ready, he said, ‘There are people behind

you who you can help, and others you can learn

from.’ And he and four other teachers had

established a three-year priest’s training program,

kind of like a divinity school, to try to train

priests to be alert to some of the hazards that

arise when you are in a position of

authority—transference, countertransference, women

being attracted to you, financial improprieties and

so on. I told him I didn’t want to be a priest but

would take the class since he asked me to. And I was

so impressed by the caliber of the other 40 or so

people in it, I followed through.

Being ordained is kind of like having a Ph.D.—you

don’t have to use it, but it is a kind of

accreditation. I wanted to step up my game, so I

ordained as a priest, and now I’m studying to

receive transmission from my teacher. I’m not sure

I’ll even use the term ‘teacher.’ My old friend Dan

Welch, one of the first students of Suzuki Roshi

[founder of the San Francisco Zen Center] uses the

term ‘Dharma Friend’ and I probably will too, to

sidestep these traps and props of hierarchy and

status, all of which are very Asian, and Japanese,

and not all of which are helpful. I’m not overly

enamored of classical Japanese Buddhism, which is

what Suzuki Roshi was seeking to escape by coming to

America. My intention is to help make Zen vernacular

here, eventually less exotic, something that would

make sense to garage mechanics and ranch hands. My

teacher and I refer to it as the ‘thousand year

project.’ So, I only wear my robes for very formal

ceremonies like weddings and funerals, and haven’t

shaved my head, as most Buddhists in the world do.

Speaking of time, you’ve lived in Marin for many

years. But now you are moving. Why?

Yes, I am moving to Sonoma County. I’ve had it with

Mill Valley. It’s become so crowded, so much

traffic, and so little responsibility has been

devoted to the carrying capacity of the area. We are

seriously overpopulated just with respect to water.

As far as I’m concerned, every successive group of

supervisors and commissioners have been bought off

by developers. I saw some of that with my own eyes.

I first came here in 1965, and loved it, and then

moved to Zen Center in the city. I returned in 1983,

as my daughter was getting mugged for her lunch

money in the Fillmore.

Twenty-five years ago I participated in a series of

meetings called ‘Take Back Our Town.’ Over 700

people showed up, and we wanted to use water as the

basis of determining population. Wanted to cut down

traffic. We even ran people for office, but the

developers outspent us six to one, and have been

building ever since.

Now traffic has reached critical mass, IT money is

coming in and bidding houses for hundreds of

thousands over asking price, all cash. It feels like

the town is filling with people who ruined and fled

the last place they lived. I walk on the marsh path

with a plastic bag picking up organic yogurt cups

and Kleenex and all sorts of trash our newly

enlightened denizens fling away at will. I’ve seen

people in Whole Foods yelling at a young mother for

being too slow to move her cart due to trying to

corral two children, and so many times people

honking and screaming at one another in their cars

for no reason—IN MILL VALLEY! Well, they’re all

stressed because it takes so much money and so much

work to live here. Couple that with the entitlement

that dictates that we are entitled to the best of

everything and you have a toxic broth in a

paradisiacal setting. I have friends here who are

not that, but we are like the proverbial frogs in

the water that is being heated slowly. Meanwhile I

am spending too much time in traffic, and it’s

maddening. The water issues will only get worse.

I feel I’ve spent 40 years fighting for this great

place, trying to preserve it, and I’m going to spend

what is likely my last vigorous decade not fighting

anymore, perhaps helping others, and leave before I

get cooked.

[ The

Official Peter

Coyote Web Site ]

|